☰

☰

aus Kurzgeschichte

Sometimes it rains through the roof, then he wakes up at night, with a sudden, rare clarity in his head, picks up a bucket and places it under the dripping spot. He has noticed that it happens more and more often, but he has not yet come to do anything about it. You’d have to call a person who can patch it up, talk to someone about money and material and things like that, which are now completely alien to him.

The house has fallen apart. Long cracks have dug into the plaster like river beds in a landscape. The ivy has grown, it is already covering some windows. And the leaves on the stone slabs change over the years into hummus, on which small, light green trees grow, which spread and will eventually burst the stone slabs with their roots. Somewhere, at some point, there was another gardener who sometimes swept away the leaves, but he can’t remember when he last saw him.

I’ve thought a lot about him, and gradually I know more about him than he does. He’s a thinker, a lost philosopher, he’s sitting in an old villa in Tuscany and he doesn’t like life, life as you know it, warm, cold, breathing out, going on or giving up. He likes to sit and he does a lot because he can think so much better and he thinks, but his thoughts get tangled up like the threads in a door frame in a strip club. He wants to go through the door once, loosen the threads, go on, see life, breathe in, breathe out, smell the air, but it doesn’t work, because he hangs in these threads and climbs up them like an animal, a very small one that can’t fly. There he climbs around in his thoughts and thinks and knows nothing. And I stand there and see him, every day when I clean the kitchen, put fresh figs on his table and think: get up. Or lie down. Or smoke a cigarette. Or jump into the swimming pool, even if there is no water. But do something so that you live. I could explain everything to him, about the threads, the figs, the world, the breathing, maybe even the love. Gladly about love. But then I think maybe he’s climbed too far up in the threads, maybe he’s too far up, and all he can do is let go and fall. I would catch him, but he would be so small and small that I would not find him, and he would fall into a crack between the stone slabs and I would look for him, but he would be gone.

A baby once drowned in the empty barrel in the inner courtyard, but he doesn’t know that. He doesn’t know much at all, not about what happened in the past and not about what will come in the future. But he likes to sit here in the courtyard of the old villa and think. He frowns and thinks about solutions, solutions for very specific things that make up the core of his life. You have to be able to explain it, there has to be a reason for all this, for the grief that sometimes knocks him down and leaves him paralyzed, for what people call joy or happiness or love. He doesn’t think so often about war, it’s a trifle, an outgrowth of the big inexplicable undergrowth that calls itself existence. He also doesn’t think about food very often, only when he opens the fridge and takes out a frozen pizza. When he eats the figs that the cleaning lady sometimes puts down for him, he does not think of the figs, but of this ball of threads in his head that have to be untangled, spread out and stretched out. One would have to tighten them, these threads that they can never move again, like guitar strings, so that one can play on them, with the precise certainty of what tone they would make of themselves. He would like to think of other things, figs for example, and perhaps even war or even peace, but he has no time until he has solved this great riddle.

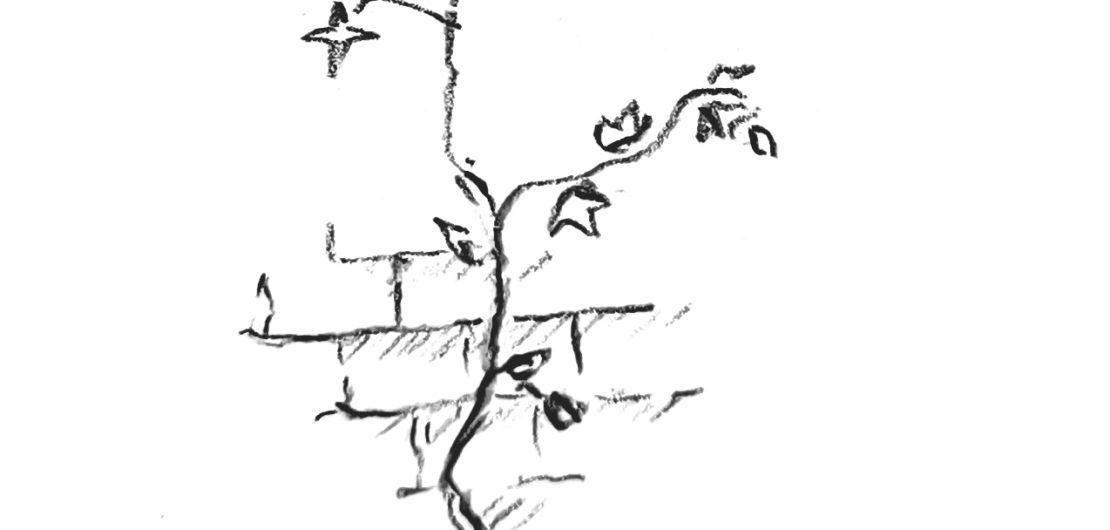

When I come in the morning to sweep away the leaves or repair a wall that has long died anyway, I sometimes see him still sitting there, somewhere, at the edge of the pool, on one of the garden furniture, too lost in thought that he had covered it, the first morning dew on the seams of his jeans. And sometimes I think he’s dead, but then he blinks and I know he’s not dead yet. But I wonder how you can be so young and yet so dead. He writes everything down. He always has a notebook in his hand, sometimes a full one, sometimes not. Sometimes I find one in the leaves of the empty swimming pool or under the garden table or on the roof, and then I ask myself: What was he doing on the roof? Maybe he’s sitting there thinking and looking down and seeing more clearly because he’s further up and has no walls around him. Sometimes I look at the notebooks, and there are strange drawings, like threads, tense and rumpled, like balls, like the balls of yarn that my mother had in wartime, that had to be stretched with both arms so that the person opposite could wind them up. There are letters and numbers, too, but I don’t understand them, they’re not words, they’re something like equations, something like I once saw in school when I flirted with the girls in chemistry class. So there he is, somewhere in this shattered, disintegrated world, drawing these threads, and I know very well that it’s all over. He has broken through a wall that my father had broken through during the war, I saw it in his eyes.

Every evening he goes back into the house and switches on the light above the kitchen table. If he had a favorite time of the day, it would be that time. His head is tired, the ball of thoughts comes to a standstill. Slowly he can let it go, because he knows that he has to sleep so that he can think again tomorrow. He eats his lukewarm frozen pizza in the room where you had played the piano in another life. Then he goes up to the bathroom, washes himself, carefully and dutifully, and goes to bed. He never reads in bed. The bed is for sleeping. He closes his eyes and usually falls instantly into a deep sleep. This moment, this millisecond of not thinking before the world of dreams receives him in its realms, is the only reason why he is still alive. But he does not know that. Neither does he know that ghosts inhabit the house with him and that one day they will drive him away and he will stand on the street with nothing but formulas in his head.

Maybe it’s the house, and everything that happened here, the thing with the dead baby and the mother who broke her legs in the empty swimming pool, something like that can’t go unnoticed in a place like this. And maybe that’s the reason why I come so rarely, more and more rarely, until nobody thinks about me anymore and everyone has forgotten that I exist because I just don’t want to see how everything dies.

Leave a Reply